A comprehensive exploration of artificial intelligence’s transformative impact on architectural practice, featuring industry leaders discussing current applications, challenges, and future possibilities.

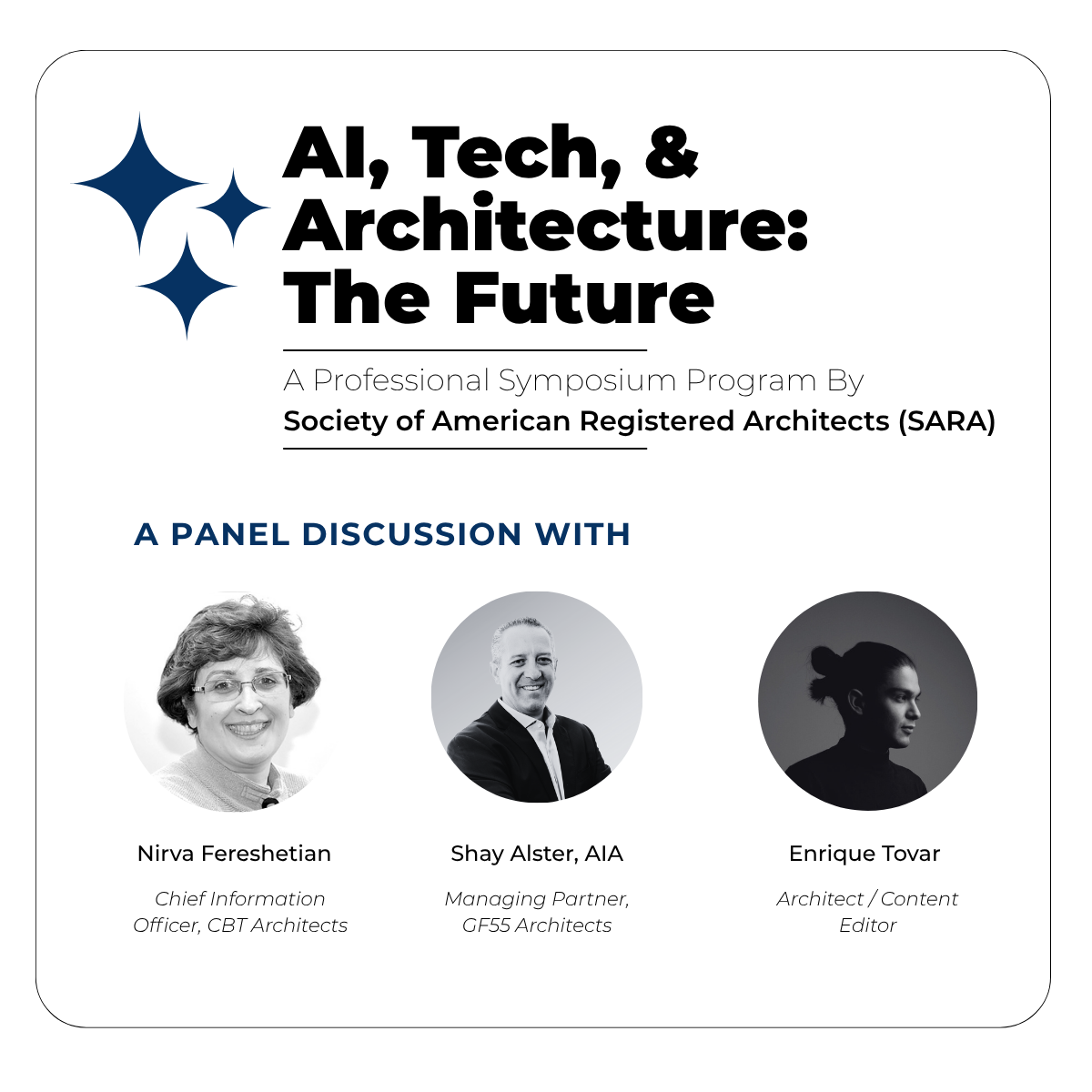

Event: Society of American Registered Architects (SARA) National Symposium Webinar 2025

Topic: AI, Tech, and Architecture: The Future

Moderated by: Michael Loussinian

Date: May 16, 2025

Panel of Experts:

- Nirva Fereshetian – Chief Information Officer, CBT Architects, Boston

- Shay Alster – Managing Partner, GF55 Architects, New York City

- Enrique Esteban Tovar – Founder, DUA (Universal Design Studio), Journalist, Writer, & Architectural Journalist

Moderator – Michael Loussinian, Assoc. SARA – Founder of Bluebuild Enterprises

The Society of American Registered Architects (SARA) National Symposium brought together leading voices in architecture & AI technology to discuss the profound impact of artificial intelligence on the architecture industry. This comprehensive discussion covered the current state of AI adoption in architectural practice, the challenges and opportunities facing firms as they integrate new technologies, and bold predictions for the future of the profession. The panelists, representing diverse perspectives from large corporate environments to specialized design studios, provided candid insights into both the promise and the practical realities of AI implementation in architecture today.

Panel Introductions: Meet the Experts:

Nirva Fereshetian is the Chief Information Officer at CBT Architects, where she brings a rare blend of expertise in both architecture and computer science. Throughout her career, she has been dedicated to implementing AEC technologies in creative and forward-thinking environments. With a deep understanding of both design and digital innovation, Nirva stands at the forefront of the industry’s technological transformation. Her unique background positions her as a key voice in the evolving conversation around AI integration in architecture, offering insight into both its vast potential and its practical constraints. At a time of significant change and opportunity in the AEC sector, she remains optimistic about the industry’s future and the role of collective innovation in shaping it.

Shay Alster is a Principal at GF55 Architects, a New York City–based firm known for its work in multifamily mixed-use residential buildings, as well as institutional, retail, and hospitality projects. With a practice rooted in efficiency and delivery, Shay brings a practical, project-driven perspective to architectural innovation. Over the years, he has guided his firm through the evolution from traditional drafting to cutting-edge digital workflows—including CAD, 3D modeling, and BIM. As the industry stands on the brink of widespread AI adoption, Shay remains focused on exploring how these tools can enhance design and production processes, carrying forward GF55’s long-standing commitment to technological advancement.

Enrique Esteban Tovar is the founder of DUA, a design studio specializing in accessibility and universal design. In addition to his work as a practitioner, he is also a journalist and writer, with a focus on AI and emerging materials over the past two years. Enrique’s dual role as both designer and commentator gives him a distinctive vantage point in the evolving dialogue around technology in architecture. As both an observer and participant in the AI revolution, he offers valuable insight into not only the technical potential of these tools but also their broader social and ethical implications.

Moderator Introduction:

Michael Loussinian is an architectural designer, entrepreneur, and AI enthusiast known for his innovative approach to integrating artificial intelligence into architectural workflows. An Associate Member of the SARA California Council, he frequently speaks at industry events and student workshops, championing the future of design through the synergy of human creativity and emerging technologies.

He leads Bluebuild Enterprises, creating smart, AI-driven design tools intended to streamline traditional drafting processes. His work emphasizes collaboration between architects and algorithms to generate more efficient and environmentally conscious building solutions. Passionate about mentorship, he also advises emerging designers on how to leverage AI responsibly in their creative practices.

Current State: AI’s Impact on Project Delivery and Performance Goals

Michael: Over the past year, how has AI improved your ability to deliver projects that meet performance goals, like occupant comfort, operational efficiency, safety, and compliance?

Shay: We’re in a very special time where things are changing fast. AI has been pretty disruptive—not just for us as a company, but for the industry as a whole. We’ve evolved from drafting with rapidographs on Mylar to 2D CAD, then 3D modeling, and BIM. That’s over 25 years of evolution. Now, we’re being asked to use AI programs. It’s a big change. Everyone’s testing things. We’re still in the R&D phase. A lot has been done with hardware and software, but data—the third piece of AI—is still developing.

We’re learning how to use AI in our practices, but we’re not yet at the point where AI can generate drawing sets or build-ready models. We’re getting there, but it’ll take time.

Shay’s perspective highlights a crucial point about the current state of the industry: while there is tremendous excitement about AI’s potential, the practical applications are still in their infancy. The comparison to the 25-year evolution from hand drafting to BIM provides important context for understanding that technological transformation in architecture is typically a gradual process, not an overnight revolution.

Nirva: The word “AI” is being thrown around with many meanings. Companies that used to do automation are now calling themselves AI companies. The term can be misleading. In the AEC industry, image generation has been the most visible use case so far—tools like MidJourney. But the gap between what we think we’re using and what AI actually is, is quite large.

This change is unlike previous ones like moving from CAD to BIM. Those were more compartmentalized. AI is both an industry and a lifestyle change. Now, even family members ask me, “Do you use AI?”—when before they didn’t even understand what I did. It’s become part of everyone’s ecosystem.

We’re focusing on exploring and educating our firm, putting tools in everyone’s hands so they can define use cases. It’s not a one-size-fits-all situation. There are thousands of tools out there, many overlapping. So for us, it’s important to ensure everyone has at least touched AI so we can collectively define where it’s useful and what problems it solves.

Nirva’s observation about the difference between this technological shift and previous ones is particularly insightful. The ubiquity of AI discussions in popular culture means that this technology transformation is happening in a much more public and socially conscious way than previous technical adoptions in architecture. Her approach of democratizing access to AI tools within the firm represents a strategic response to this challenge.

Enrique: I’d like to echo Nirva’s point: this is a lifestyle change. As a designer and a journalist, I think we need to be responsible in how we engage with AI—understanding the difference between visual novelty and actual design logic.

A lot of AI-generated images online don’t reflect a design process. AI is a co-pilot, not a decision-maker. We must stay critical and intentional. For example, AI motivated me to start learning code—something I never thought I’d do as an architect. There’s a multidisciplinary opportunity here, especially as we engage with developers and software creators.

Enrique’s emphasis on the distinction between “visual novelty and actual design logic” touches on a critical concern in the current AI landscape. The proliferation of visually striking AI-generated architectural images on social media and design platforms has created confusion about what constitutes meaningful AI application in design practice. His personal journey of learning to code as a result of AI engagement demonstrates how these tools can catalyze broader professional development.

Strategic Applications: Balancing Creative Ambitions with Practical Constraints

Michael: As AI continues to evolve, where do you see it having the greatest impact, especially when balancing creative ambitions with practical constraints like budget, code compliance, or long-term performance?

Enrique: There’s a general concern about AI diminishing human creativity. But I think it’s actually going to make us more intentional. I once tried using ChatGPT to analyze images for accessibility. It gave me specific issues but couldn’t understand the big picture. That’s where human experience still plays the key role.

Younger generations are more eager to use AI, while others may hesitate. This creates a generational gap that design firms must navigate. Last night, I read a book comparing AI’s impact to the printing press—it made me realize how significant this shift really is.

The accessibility analysis example Enrique provides is particularly telling about current AI limitations. While AI can identify specific technical compliance issues, it lacks the holistic understanding of how spaces function for users with different abilities. This limitation illustrates why human expertise remains crucial, even as AI capabilities expand. The generational divide he mentions is a common theme across many industries adopting AI technologies.

Nirva: AI has the potential to impact every part of our process—from idea generation to compliance checks to building performance studies. We already use tools for shadow studies, acoustic analysis, and carbon footprint evaluation. All of those things are really really essential tools.

The challenge isn’t resistance, it’s capacity. We’re busy. Learning new tools while meeting deadlines is hard. Sometimes, I worry that we’re teaching tools more than the profession itself. Many tools also aren’t fully ready. There’s initial excitement, but then the realization that users still need to do a lot manually.

We are big proponents of contributing to the development of these tools. We test, give feedback, and work with developers to move things forward. I love the quote someone mentioned earlier: “Let AI do my laundry and dishes—leave the writing to me.” We want AI to handle the mundane so we can focus on creativity, but it takes effort to train it to do so.

Nirva’s point about capacity versus resistance is crucial for understanding the real barriers to AI adoption in architecture. The profession’s traditionally demanding schedules and tight project deadlines create a challenging environment for learning new tools. Her concern about “teaching tools more than the profession itself” raises important questions about educational priorities and professional development in an AI-enabled future.

Shay: I agree with Nirva—there’s no true resistance to AI, just hesitation due to deadlines and unfamiliarity. There’s a natural discomfort with things we don’t know. Also, there’s a fear: will AI replace me as a designer?

But the greatest potential I see is when we integrate AI across all project players—architects, developers, contractors, financiers. If we can use AI to streamline collaboration, considering construction methods, specs, and costs all in one system, then the promise of AI will be fulfilled. Until then, it’s up to us professionals to keep testing and pushing.

Shay’s vision of integrated AI across all project stakeholders represents one of the most ambitious and potentially transformative applications of the technology. The current fragmentation of the construction industry, with each discipline using different tools and workflows, creates significant inefficiencies. AI-enabled integration could address fundamental industry challenges that have persisted for decades.

Implementation Strategies: Custom Tools vs. Existing Solutions

Michael: Are your teams building custom tools or adapting existing ones? And how is that impacting client and regulatory expectations?

Enrique: I think we’re heading toward more custom tools. AI works well for feasibility studies. But for areas like accessibility, there’s still no specialized tool. In the future, I see tools that let us control more parameters like materials, scale, or atmosphere.

As AI starts automating routine tasks, we’ll spend more time thinking creatively. But the emotional and sensory aspects of design—like the atmosphere of a space—can’t be digitized easily. So the human role stays essential.

Enrique’s observation about the lack of specialized accessibility tools highlights a broader issue in AI development for architecture: many niche areas of practice remain underserved by current AI offerings. His insight about the difficulty of digitizing “emotional and sensory aspects” touches on fundamental questions about what aspects of design can and should be automated.

Shay: Custom tools may be useful for specific tasks. Some companies are working on NLP (natural language processing) and speech-based design tools. But like Nirva said earlier, we’re not at the point where one place or one tool can do it all. Until then, we’ll keep complementing existing tools as best we can.

The mention of NLP and speech-based design tools points to an emerging area of AI application that could significantly change how architects interact with design software. The ability to describe design intent in natural language and have software interpret and execute those instructions represents a fundamental shift from the current GUI-based design tools.

Nirva: Custom tools depend on company size and goals. Building a full application is a big commitment—you also need to maintain it.

Instead, I see a lot of value in AI agents—small automations for repetitive tasks, often voice-activated or built into existing tools like Microsoft Copilot. They’re not full applications, but they can really help.

Rather than focusing on the tool itself, I want us to focus on our value proposition as a firm. If AI automates the basics, what makes our firm different? That’s a good exercise.

One major need is fixing our datasets. Machine learning depends on high-quality data, and a lot of our older data isn’t valid. We’re working on cleaning and standardizing it—starting with our detail library. But that’s a team-wide effort.

Nirva’s emphasis on data quality represents one of the most practical and immediate challenges facing firms implementing AI. The architectural profession has decades of digital files that were created for human use, not machine learning. The effort required to clean and standardize this legacy data is substantial but necessary for effective AI implementation.

Deep Dive: Understanding AI Agents and Their Applications

Michael: Could you explain “AI agents” for those who might not be familiar?

Nirva: One example is Microsoft 365 Copilot. We’re rolling it out across our office. It summarizes emails, meeting notes, and offers task suggestions.

Inside that system, you can create simple “agents”—automated sequences for tasks you repeat often. More advanced AI agents also exist across platforms, and I think these will help us automate without needing to build full custom apps.

The concept of AI agents represents a more accessible entry point for most firms compared to developing custom AI applications. By leveraging existing platforms like Microsoft 365, firms can begin to experience AI benefits without significant technical investment or expertise.

Enrique: Yes, and as Nirva said earlier—AI is only as good as its data. Blueprints and plans are valuable, but they need to be cleaned and structured for AI to work. In time, AI will be more embedded in everything. Eventually, interacting with it will become second nature.

Shay: Exactly. The AI’s output is only as good as what we feed into it. Prompting and clean data are essential. We want creative, meaningful results—but that takes learning and experimentation. AI is not plug-and-play—it’s a process.

The repeated emphasis on data quality and the learning process required for effective AI use underscores a key misconception about AI adoption. Unlike traditional software tools that can be learned through training manuals or tutorials, AI tools require ongoing experimentation and refinement of approach.

Future Visions: Predictions and Possibilities for the Next Five Years

Michael: Where do you see AI going in the next five years? What should we expect?

Nirva: Predicting the future right now is dangerous—things are moving too fast. What I hope to see is fundamental change in our industry to support this technology. That means changes in contracts, collaboration, workflows.

Right now, even with CAD and BIM, our deliverables haven’t drastically changed—we’re still giving PDFs. We’re digitized, but not necessarily thinking digitally. I hope AI pushes us to truly shift. Every project phase starts over from scratch; nothing flows downstream smoothly. We’re still seen as an inefficient industry. That’s what I want to change.

Nirva’s observation about the industry being “digitized but not thinking digitally” is particularly astute. Despite decades of digital tool adoption, many architectural workflows still mirror pre-digital processes. This represents both a challenge and an opportunity for AI implementation—the technology could catalyze more fundamental process improvements.

Shay: I’ll take a small risk and make a few predictions. First, decision-making will still remain in human hands—for now. We’ll be the ones evaluating what AI gives us, and choosing what to accept or reject.

Second, we need to identify areas where AI can improve efficiency. And we need to test. Only by diving in and testing can we understand where AI works best.

In the long run, the biggest benefit will be collaboration. I see architects, contractors, developers, even banks and insurers using AI tools together—finally working in sync. But we have to understand how our staff is using these tools so we, as business leaders, can make smart decisions.

Enrique: My focus is on integration. I work with existing buildings, and I’m seeing exciting overlaps with LIDAR scanning, 3D modeling, and digital twins. AI can help us use scanned data to create better models and design outcomes.

This came up at the Venice Biennale, actually—the crossover between physical space and tech. Instead of worrying about AI replacing humans, we should focus on using the right tool for the right task.

We’re also seeing a shift toward reusing buildings—because it’s more sustainable. AI can help us understand those structures and optimize how we reuse them.

Enrique’s focus on building reuse and renovation, combined with AI analysis of existing conditions, represents a particularly timely application given current sustainability concerns. The ability to rapidly analyze and understand existing buildings through AI-enhanced scanning and modeling could significantly improve the efficiency and effectiveness of renovation projects.

Technical Implementation: Training AI for Local Codes and Constraints

Michael: How much teaching and training would an AI need to perform well on a project with respect to things like local codes, weather conditions, and budget constraints? And more broadly — “Is the goal to eventually have one universal AI program, or will every professional develop their own tools?“

Nirva: I don’t believe there’ll be just one AI tool for everyone. Every platform we already use — Photoshop, finance software, even our image asset manager — has some AI component baked in. It’s becoming ubiquitous.

The issue now is personalization. Prompts are personal. How people use the tools is personal. So training people on AI is nothing like training someone on Revit — it’s not about where the button is, it’s about learning how to think with the tool.

We’re encouraging staff to look past what a tool can do today and instead focus on its roadmap. If we only judge based on current results, we’ll miss the point.

The personalization aspect of AI tools represents a fundamental shift in how architectural technology works. Traditional CAD and BIM software has standardized interfaces and workflows, making training relatively straightforward. AI tools, with their reliance on natural language prompts and contextual understanding, require a more individualized approach to mastery.

Shay: There are thousands of tools — I’ve seen estimates of 7,000+ AI tools for different sectors. Even within architecture, there’s no “one place” that does everything. Tools specialize — some are great for renderings, others for code analysis, others for site studies.

Even the same tool can produce different outcomes depending on how it’s used. That’s what makes this so personal and fluid — it’s less like “training” and more like experimenting until you find what works for you.

The proliferation of AI tools creates both opportunities and challenges for architectural firms. While the variety ensures that specialized needs can be addressed, it also creates complexity in tool selection and integration. The experimental nature of AI tool usage requires a different approach to technology adoption than traditional software implementation.

Key Themes and Takeaways from the Discussion

The Reality Gap Between AI Promise and Current Practice

Throughout the discussion, panelists consistently emphasized the gap between the current capabilities of AI tools and the ambitious promises often associated with them. While image generation tools like MidJourney have captured attention, the practical applications for day-to-day architectural practice remain limited. This honest assessment helps set realistic expectations for firms considering AI adoption.

Data Quality as a Foundation for Success

Multiple panelists stressed that AI is only as good as the data it processes. For architectural firms, this means confronting decades of digital files created for human use, not machine learning. The effort required to clean, standardize, and structure legacy data represents a significant but necessary investment for effective AI implementation.

Personalization and Individual Learning Curves

Unlike traditional software training, AI tools require personalized approaches to mastery. The reliance on natural language prompts and contextual understanding means that each user must develop their own expertise through experimentation and practice. This has implications for how firms approach training and professional development.

Collaborative Potential Across Disciplines

Perhaps the most exciting long-term possibility discussed was AI’s potential to enable better collaboration across the fragmented construction industry. By providing common platforms and tools that can be used by architects, engineers, contractors, and other stakeholders, AI could address fundamental inefficiencies in building project delivery.

The Need for Industry Structure Changes

Several panelists noted that realizing AI’s full potential will require changes beyond just adopting new tools. Contracts, workflows, and collaborative relationships may need to evolve to fully leverage AI capabilities. This suggests that the AI transformation in architecture will be as much about business model innovation as technological adoption.

Implications for Architectural Practice

For Firm Leadership

Leaders must balance the pressure to adopt AI with the practical challenges of implementation. The discussion suggests focusing on experimentation and gradual integration rather than wholesale transformation. Understanding how staff members are using AI tools becomes crucial for making strategic decisions.

For Individual Practitioners

Architects at all levels should begin experimenting with AI tools to develop personal expertise. The personalized nature of AI interaction means that hands-on experience is essential for developing proficiency. However, practitioners should maintain critical thinking about AI outputs and continue to rely on professional judgment.

For Architectural Education

The discussion raises questions about how architectural education should adapt to an AI-enabled future. While technical skills remain important, the emphasis may shift toward developing critical thinking about AI outputs and understanding how to effectively collaborate with AI tools.

For Technology Developers

The panel’s feedback suggests that tool developers should focus on integration with existing workflows rather than creating entirely new platforms. The emphasis on data quality and user-friendly interfaces for non-programmers also provides guidance for product development priorities.

Conclusion: Embracing Change While Maintaining Professional Values

The SARA National Symposium discussion reveals an industry at a pivotal moment. While AI technologies offer tremendous potential for improving efficiency, enhancing collaboration, and enabling new forms of design exploration, the path forward requires careful consideration of practical constraints and professional values.

The panelists’ experiences suggest that successful AI adoption will be gradual, experimental, and highly dependent on individual firm contexts and goals. Rather than a single technological solution, AI represents a collection of tools and approaches that must be thoughtfully integrated into existing practice.

Perhaps most importantly, the discussion emphasizes that AI should be viewed as a collaborative partner rather than a replacement for human expertise. The technology’s ability to handle routine tasks and process large amounts of data can free architects to focus on the creative, strategic, and interpersonal aspects of practice that remain uniquely human.

As the industry continues to evolve, the insights shared in this symposium provide valuable guidance for navigating the opportunities and challenges ahead. The future of AI in architecture will be shaped not just by technological capabilities, but by how thoughtfully and strategically the profession chooses to embrace and implement these powerful new tools.